Cancer is a complex disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and by the ability of tumour cells to invade healthy tissues. It is currently the second leading cause of death worldwide, and its complexity is closely linked to the great genetic and functional diversity of tumours. This heterogeneity makes both early diagnosis and the development of effective therapies challenging: each tumour has unique features and, even within the same cancer type, cells can adapt to treatments and escape the natural regulatory mechanisms present in the body.

Within this context lies the InhiBIT project, led by Professor Giusy Tassone of the Department of Biotechnology, Chemistry and Pharmacy at the University of Siena. The name InhiBIT is an acronym for “Inhibiting 14-3-3/BAX complex Interactions for Cancer Therapy.” This term perfectly reflects the aim of the research: to “inhibit” the interaction between two proteins, 14-3-3 and BAX, whose complex plays a crucial role in regulating cell survival.

“The ultimate goal of the project,” explains Professor Tassone, “is to generate new molecular knowledge that can support more targeted and personalized therapeutic strategies, increase treatment efficacy while reduce side effects, with the aim of significantly improving patient prognosis.”

In healthy cells, the protein BAX (a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family) is responsible for activating apoptosis, the programmed cell death process that allows the organism to orderly eliminate damaged or no longer needed cells. This mechanism is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis and preventing the accumulation of potentially harmful cells.

However, in cancer cells this function is hindered by 14-3-3 proteins. “These proteins”, the researcher continues, “form a family of seven isoforms involved in fundamental cellular processes such as survival and proliferation. In many tumours, they are overexpressed and act as true signalling hubs, promoting tumour growth”. In this way, cancer cells are able to evade normal control mechanisms, favouring disease progression and making treatment more difficult.

Although they are not classic drug targets, 14-3-3 proteins represent an extremely promising one. The researcher further explains the mechanism: “Some isoforms, such as ε, τ, σ and ζ, bind to BAX. Under normal conditions, BAX is activated in response to stress signals and translocases to the mitochondria to trigger apoptosis; however, when it interacts with 14-3-3 proteins, it remains inactive in the cytoplasm and the process is blocked, allowing cancer cells to survive. Disrupting this interaction could therefore reactivate BAX and restore programmed cell death in malignant cells”.

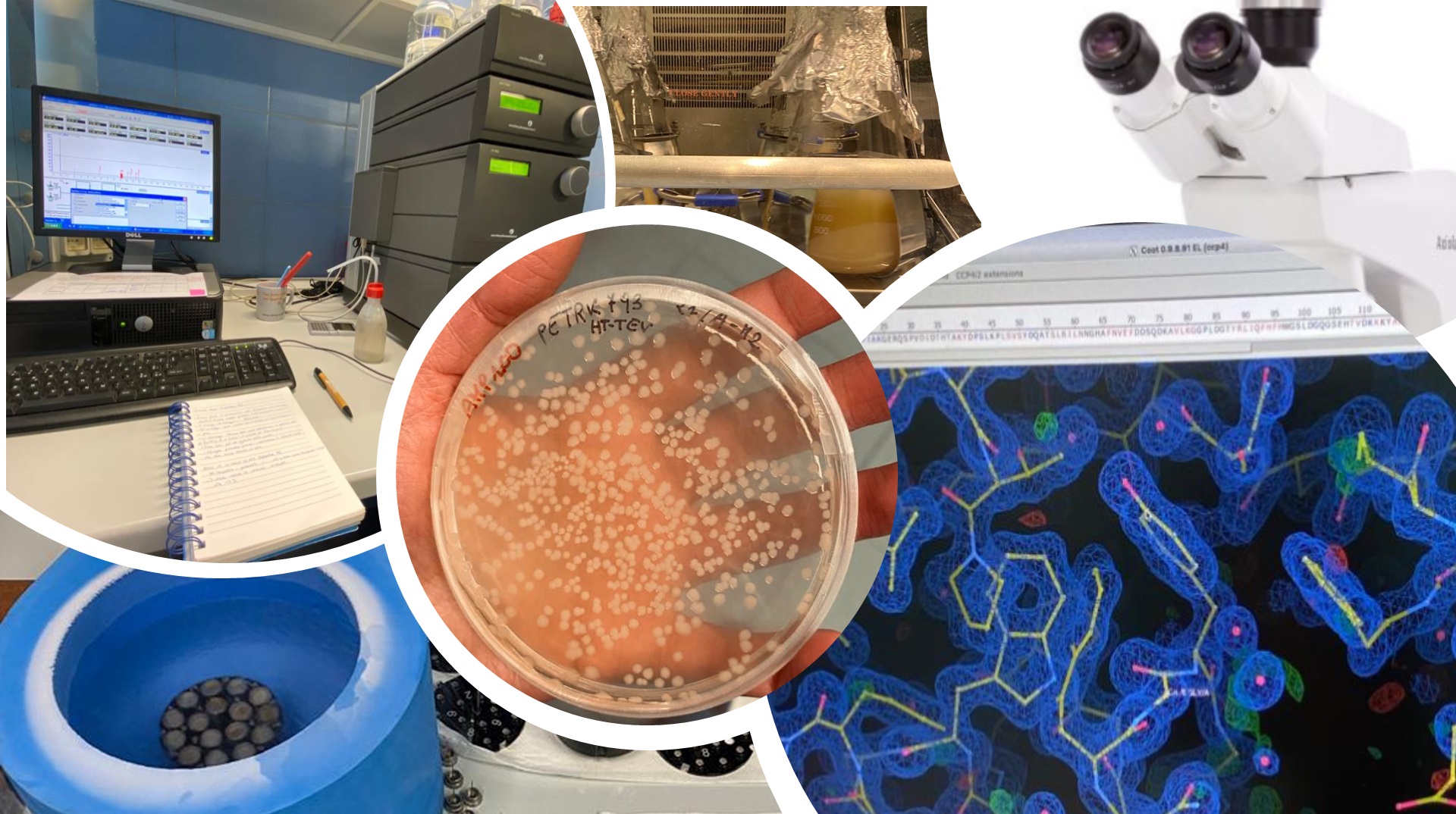

To achieve this goal, InhiBIT combines molecular biology, biochemistry and structural biology techniques. The 14-3-3 and BAX proteins are produced as recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli, a well-established and efficient expression system. Their interaction is then confirmed through biochemical assays, while structural characterization of the complexes is carried out using state-of-the-art technologies.

“We use X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM)”, explains Tassone, “which allow us to observe in detail the arrangement of the proteins and the specific contact residues between 14-3-3 isoforms and BAX. This structural information is essential to understand how to selectively block the interaction without interfering with other cellular functions, paving the way for more precise and safer drug

design”.

The research group has already achieved tangible progress: so far, the project has yielded crystals of three 14-3-3 protein isoforms, providing high-resolution structures that are fundamental for understanding their features. At the same time, expression and production trials of recombinant BAX protein have been initiated, which are necessary to complete the study of the complexes.

The ultimate aim of InhiBIT remains the generation of new knowledge on the interactions between 14-3-3 and BAX, building a solid foundation for future drug development studies. “This information”, concludes Professor Tassone, “may contribute to the development of innovative and targeted therapies, representing a step forward toward personalized cancer treatments and improving both quality and life expectancy for patients.”